Though Alvar Aalto is considered not only one of the greatest architects of the 20th century but a central figure of the modernist movement, many people outside of Scandinavia are probably unfamiliar with his name. This probably has less to do with the fact that Aalto was Finnish than with the eventual impact of his work over the years. Though Aalto did see himself as an artist, with the stereotypical free-ranging behavior to prove it, he saw his mission as a designer in humanist terms, an attitude that’s most apparent in the furniture he made. In that regard, it’s important to mention his first wife, Aino, who was also a trained architect (and a trained carpenter to boot, which her husband wasn’t) with a more patient approach to commerce. One thing that this documentary by Virpi Suutari gets very right is the way it presents the title as a kind of brand made up of both Alvar and Aino. If Alvar still gets the lion’s share of the credit for the enduring utility and beauty of the things they created together, it’s mainly because he was good at promoting those things in the world, while Aino mostly stayed at home and ran the day-to-day business. He never denied her her rightful share of the glory.

As a movie, Aalto is endlessly involving but also frustrating in its inability to really convey the Aaltos’ mission of making things that were, first and foremost, human scale. Apparently, “aalto” in Finnish also means “wave,” and what most people notice first of all about the designs, whether applied to buildings or furniture, is their curvilinear aspect. The chairs that the couple made for their company Artek in the 1930s and 40s originated that now common look of one piece of wood steam-bent into a form that fits the body, but the curve is also what makes the famous Baker House at MIT so striking. And while Suutari does take us into the buildings, we rarely get a sense of how they are used since the people inhabiting them on screen seem more decorative than anything else. Still, the sheer volume of work that Alvar accomplished even after Aino died in 1949 and he took on a new wife/work partner, Elissa, several years later is astounding: 300 finished projects and 200 unrealized ones. And while Aalto did do the occasional design for private residences—the homes he made for himself and others in Finland achieve the near impossible feat of looking minimal on the outside while providing maximum space on the inside—his strong suit was public buildings that are marvels of light and form. His one seeming failure was also his most ambitious, the Helsinki City Center, which some felt was so grandiose as to be uninviting, though to me it looks fabulous.

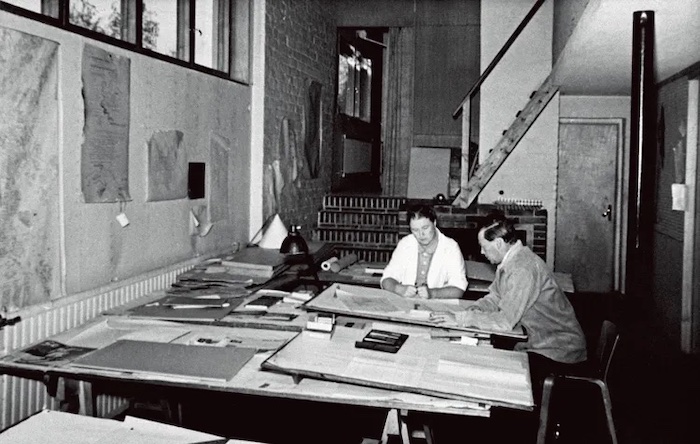

As for Aalto’s personality, Suutari uses the architect’s own words, mainly in the many letters he wrote to Aino while travelling to America and Europe for commissions. Though I’m not sure if the infidelities he so boldly alluded to in these epistles (“you need to commit a whole lot of sin before we’re even”), or the drinking that Aino constantly chides him about best reveal his bohemian temperament, as Suutari seems to imply, they do reveal his own humanity. What interested me more was his approach to work, especially work with others. By all accounts he was a good boss, encouraging his employees to think for themselves even if, in the end, he had the last say. He even had great respect for the tradesmen who carried out his projects and worked closely with them, which was not something that most of his peers did. On the other hand, he was highly impressionable, and would easily lift ideas from others without acknowledgement. Upon meeting the dapper Frank Lloyd Wright, he even started dressing like him. Genius comes in many forms, but Aalto makes the case that ideally it has room for a democratic, inclusive spirit.

In Finnish, English, German, Italian and French. Now playing in Tokyo at Human Trust Cinema Yurakucho (03-6259-8608), and from Oct. 28 at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum Ebisu (03-3280-0099).

Aalto home page in Japanese

photo (c) FI 2020 – Euphoria Film