Last week the Gunma prefectural government removed a monument from a park in the city of Takasaki that commemorated Korean laborers mobilized to work in the prefecture during World War II. The monument was installed in the park in 2004, but in 2014 the prefectural government refused to renew the permit for it, saying that the citizens group that petitioned to have it placed in the park had violated one of the conditions for its installation, which is that the group not hold “political events” related to the monument. Apparently, during a memorial ceremony a member of the group had referred to the Koreans it honors as having been “forcibly mobilized,” a situation the Japanese government denies. When the monument was removed, there was a large contingent of police on hand to make sure people who were protesting the removal did not clash with right wing groups who approved of the removal.

Prior to the removal the web talk show No Hate TV covered the matter in relation to the issue of forced Korean labor during the war. The governor of Gunma insisted that the removal had nothing to do with “historical awareness” but was simply an unavoidable response to the citizens group’s “breaking a rule,” though no one really believes that. Ruling Liberal Democratic Party lawmaker Mio Sugita, a well-known right-wing politician, publicly said that she agrees with the removal of the monument because it commemorates what she calls a lie. However, as the discussions on No Hate TV elucidated, the forced mobilization of workers from Korea, then a Japanese colony, for the war effort has been acknowledged by historians as a fact, at least with regard to some of the workers. The Japanese government has acknowledged, albeit tacitly, that some Chinese workers were forcibly mobilized during the war, but not Koreans.

During the discussions on No Hate TV, one of the unavoidable historical incidents that came up was the sinking of the transport ship Ukishima-maru in Maizuru Bay on the Japan sea coast in August 1945. According to the government, the ship was carrying more than 3,700 Korean workers from the Shimokita peninsula to Pusan in the wake of Japan’s August 15 surrender when it hit a U.S. mine while entering the harbor. The government estimated that 524 Koreans lost their lives, but survivors and others have disputed this number, saying it was much higher. In any case, the government has never carried out a proper investigation of the incident and in 1993 survivors and families of people who died sued the government in Kyoto District Court, demanding an apology and compensation, which, after an initial trial and the usual series of appeals, was eventually denied. Another matter discussed on No Hate TV was the Japanese media’s coverage of the Ukishima-maru Incident, as it’s called. The show’s host, Yasumichi Noma, said that at least two long Japanese reports on the sinking and its controversial aftermath were produced in the past, one by NHK in 1977 and another by Mainichi Broadcasting System. NHK’s report is presently unavailable for public viewing, but the MBS report, first broadcast in 1994, was on YouTube when Noma talked about it, though he predicted it might be removed, and in fact it was a few weeks ago with no reason given. (There is also a Japanese feature film made in the 1990s about the tragedy that is frank about discrimination against Korean workers. It is still available on YouTube.)

We were able to watch the MBS special partially before it was taken down, and it included an explanation of the “mystery” surrounding the sinking of the ship, along with testimonies of then still surviving passengers and other Koreans who had worked on the Shimokita peninsula during the war. The point of the lawsuit was to force the Japanese government to reveal all it knew about the Ukishima-maru Incident. The MBS report mostly takes for granted the notion that many of the Korean laborers were not only forced to work in Japan but were also abused by supervisors. Especially toward the end of the war, the work became very difficult and even deadly, since it involved fortifying the northern part of Honshu in preparation for attacks. Tunnels, railways, and air fields had to be quickly built and reinforced with minimal materials. Japanese locals who were alive at the time told MBS that the Korean workers lived under even harsher conditions than they did, and were fed sparingly. Those who died were dumped in a temple graveyard with no ceremony or markings. According to documents seen by MBS, the labor shortage just became worse as the war continued. In April 1944 alone, the regional Imperial Navy headquarters in Ominato, Aomori Prefecture, requisitioned 9,000 laborers from the Korean peninsula, and although the request mentioned that the middlemen who were tasked with providing these workers must “treat them well,” it’s obvious from the very nature of the request that the workers were not coming voluntarily. In any case, survivors said they did not know what kind of work they would be doing. Former Japanese military personnel told MBS that Korean workers were not treated any differently than Japanese workers, but at least one Japanese worker said that the Koreans were given the harsher jobs.

The question at the heart of the MBS report is what really happened to the Ukishima-maru. A detailed analysis of the incident was presented in English by scholars Jonathan Bull and Steven Ivings in the Asia-Pacific Journal in Nov. 2020, but mainly in the context of repatriation of both Japanese and Koreans after the war. The article recounts how in December 1945 the chairman of the Aomori Regional Office of the Korean Association in Japan accused the Japanese military of war crimes in the deliberate sinking of the Ukishima-maru, but the Supreme Command of the Allied Powers, after studying the claims, concluded that there was not enough evidence for the case to go to trial, and it was dropped.

An article that appeared in August 2022 in Gendai Business by the photojournalist Koji Ito is one of the more thorough media reports on the matter in Japanese. Ito has been researching the sinking of the ship for many years, and visited survivors in both South and North Korea, both of which continue to criticize the Japanese government for refusing to reveal what it knows about the incident. North Korea insists that the sinking was actually engineered by the Japanese military as a “form of revenge” after its surrender on August 15, 1945. Though Ito’s article does not reach a definite conclusion to that effect, it does raise many questions regarding the officially accepted narrative surrounding the tragedy.

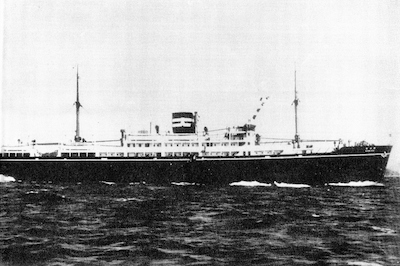

The Ukishima-maru was built in 1937 as a passenger/cargo ship: 4,370 tons and 107 meters long. In September 1941, it was commandeered by the Japanese military, as were all civilian vessels during the war. Eventually, it was based at Ominato in Aomori Prefecture, which covered not only the Shimokita peninsula but also as far north as Karafuto, currently Sakhalin. It replaced the ferry between Aomori and Hakodate on Hokkaido after the real ferry was attacked by Allied bombers. When the emperor announced Japan’s surrender on Aug. 15, 1945, the Ukishima-maru was sailing from Aomori to Hakodate, and on Aug. 18 it was docked at Ominato. The local military suddenly decided to repatriate thousands of Korean workers to Pusan using the Ukishima-maru, and the boat sailed on Aug. 22. It entered Maizuru Bay on Aug. 24 and hit a mine at 5:20 p.m., about 300 meters from the shore.

Ito says that there were questions right from the start. Why did the ship keep close to the Japan Sea coast and not sail in a direct line to Pusan? Why did it stop in Maizuru Harbor? Why did the military authority in Ominato decide to send the workers back to Korea only a week after the surrender? Repatriation of other Koreans in Japan didn’t start until late September. Ito went directly to Ominato to find out as much as he could. As already mentioned in the MBS report, as well as a 1996 South Korean documentary about the incident, Korean workers on the Shimokita peninsula were treated harshly because the local military was under pressure to get the area fortified in the event of an invasion. Many, he learned, were farmers in Korea who lost their livelihoods during colonization—the Japanese colonizers either took their land outright or taxed them so heavily they couldn’t make a living. Village leaders were charged by Japanese military authorities to requisition men for work in Japan, regardless of whether these men had families. Some were teenagers, while others said they were told they would only be needed for 6 months, but they ended up staying and working in Japan indefinitely, usually with only one day off per month. There were protests and riots that were put down brutally, but, in any case, there was no escape because they were in Japan.

Technically, they were Japanese nationals until Aug. 15, 1945, when they suddenly became foreigners, and according to Ito’s interviews it appears the local military authority was anxious about what these workers would do after Japan lost. They feared retribution and decided to send them back to Korea as soon as possible, even if some of the Koreans had already made lives for themselves in Japan and had nothing to “return to.” The Ominato authority received permission from the naval ministry to place them on the Ukishima-maru for transport to Pusan. Ito cites an interview with the chief engineer of the Ukishima-maru in the NHK documentary who said the ship’s captain told him they had to send the Koreans back before they “started a riot.” Officially, the reason for repatriation was the belief that the Koreans themselves were afraid of what would happen to them once Allied forces arrived in Japan, an assumption Ito found difficult to believe.

In any case, the situation was chaotic during the week after the surrender, and all Korean workers in the area were ordered to report to Ominato harbor by Aug. 21. Just as they had been forced to leave Korea, they were now being forced to leave Japan. Survivors all say that the ship was packed and that crew had to construct new makeshift toilets to handle the numbers on board for the journey.

But Ito discovered also that the Japanese crew were against the repatriation, since they would have to accompany the returnees to Pusan and didn’t know what kind of reception they would receive as Japanese when they arrived. Would they be arrested? Or even killed? An Asahi Shimbun report published in August 1993 quoted a military policeman as saying that the crew tried to stop the operation on Aug. 22 but could do nothing to prevent it from setting sail, and so they tried to think of other ways to make sure the ship didn’t enter Pusan. When Japanese soldiers in the area heard about the surrender, many assumed the war was over and started packing their things to go home, including the crew of the Ukishima-maru, and so when the order came down that they had to do at least one more mission, and one that was potentially very dangerous, they were understandably angry. One Korean book about the incident claims that the crew plotted to sabotage the boat, and an engineer interviewed for the NHK documentary said that all members of the crew “knew how to destroy the ship” because they had all worked in the engine room at one time. Some of the survivors Ito talked to, including one Korean who was a military policeman assigned to the boat, said they heard rumors after they boarded that the ship would be sabotaged.

Another development that invited scrutiny is that in the immediate wake of the surrender Allied forces ordered the Japanese military to send telegrams to naval facilities forbidding all large vessels from being in movement on the water after Aug. 24. Ito reports that records show the telegram was sent to the captain of the Ukishima-maru twice, at 1520 and 1535, on Aug. 22 saying that the ship must be docked by 1800 on Aug. 24. If it was on the seas at that time, then it was required to go to the nearest harbor and drop anchor. The Ukishima-maru set sail from Ominato at 2200 on Aug. 22. Even if it sailed directly, it would not be able to reach Pusan by 1800 on Aug. 24. At any rate, it sailed along the coast, and Maizuru was the only military port where it could dock by the cutoff time. According to the NHK documentary, there was a belief among the crew that once they docked in Maizuru, the Korean passengers would be someone else’s problem. In that sense, there is a valid reason for the ship stopping off in Maizuru, but many other riddles remain.

Witnesses say the Ukishima-maru dropped anchor after it entered Maizuru Bay and then pulled the anchor up and proceeded closer to the port. A half-hour later there was a massive explosion that split the ship in half. Local residents saw the explosion and took small boats out to the wreckage to save as many people as they could. The water there was about 70 meters deep.

Because the official cause of the explosion was determined to be a mine, the tragedy was classified as an act of God, and thus the Japanese government could not be held responsible. Ito cites a Japanese book about the war that states American B-22s dropped mines in the middle of the night into Maizuru Bay using parachutes, and typically Japanese mine sweepers would find the mines the next day and detonate them. Of course, they couldn’t find all the mines that were dropped, and it was estimated that about 200 were still live in the waters around Maizuru at the end of the war. All told, 8 Japanese ships came in contact with mines around Maizuru, and 4 of them sank, not counting the Ukishima-maru. The main riddle surrounding the mine is why Ukishima-maru hit a mine when dozens of other ships had already entered the bay on the same day and by the same route and did not encounter any mines. Another mystery surrounds the account of the explosion by witnesses, none of whom said they saw a column of water, which should be expected from an exploding mine. Even the Japanese bridge commander said he didn’t see a column of water, thus suggesting that the explosion was not caused by a device external to the vessel.

A close examination of the wreckage could have determined the real source of the explosion, but the owner of Ukishima-maru decided it would be too difficult to salvage the two halves. It wasn’t until after the Korean War started and the price of steel skyrocketed that parts of the wreckage were salvaged for scrap, but by then there was no compelling argument for the authorities to study the wreckage to determine the cause of the explosion. Even less important, it seems, were the remains of the victims. Japan-resident Korean groups had lobbied for the remains to be recovered for years but received no response from the government. Salvage work didn’t commence until January 1954, almost ten years after the incident.

Nevertheless, a photographer did take pictures of the wreckage, and while the film negatives have not been located, photos published in an Osaka newspaper showed that the nature of the damage to the hull indicated that the explosion likely came from within the vessel, meaning it couldn’t have been caused by a mine.

Then there is the question of exactly how many people died in the explosion. The government has always maintained that 3,735 Koreans were on the ship, but survivors all said that the vessel was so crowded that it was almost impossible to move about. Estimates from people who were witnesses to the repatriation effort think the number was more like 7,500 to 13,000. One Japanese officer interviewed said that, based on the number of Koreans who had to remain above-deck because of overcrowding below decks, there would have been at least 6,000 passengers. As for the number that died, the official number of 524 is considered implausible. It’s more likely in the thousands. When NHK asked a government official about the number, they were given a confusing answer regarding the number of femurs versus pelvic bones found. In any case, the number has never changed over the years despite subsequent third-party investigations, including one in 2007 carried out by the South Korean government. The fact that the number has never changed is in and of itself suspicious. At the very least, says Ito, the government is guilty of neglect in its handling of one of the deadliest marine accidents in Japanese history. He says it isn’t too late for the government to search for more remains since, so far, the only remains recovered were those in the salvaged wreckage.

As part of the discussions on No Hate TV, Noma interviewed Yujin Fuse, a journalist who has covered Japan’s Self-Defense Forces extensively and studied the Ukishima-maru Incident. Fuse said that the more research he’s done on the topic, the more questions he has. His main one is the original: Why were these workers repatriated only one week after surrender? His theory is that the Soviet Union, which joined the war only a week or so before the surrender, still threatened the northern part of Japan after Aug. 15, and that in the event of a Soviet invasion of Aomori, the military was afraid of how the thousands of Korean workers on the Shimokita peninsula would react. He also believes that, knowing how the workers had been treated, the authorities were afraid what they might say to Allied forces and others. But even more perplexing was the response he got when he asked the relevant ministries for documents related to the lawsuit brought by Korean survivors in the 1990s. The documents supposedly include minutes of discussions among Japanese officials about the Ukishima-maru Incident, but the only thing he could obtain was the cover page of the minutes, and it was completely redacted. The minutes themselves weren’t included in the pages Fuse received. As Noma pointed out, if the sinking of the Ukishima-maru was really an “accident,” as the government claims, they should have nothing to hide, but apparently they do.