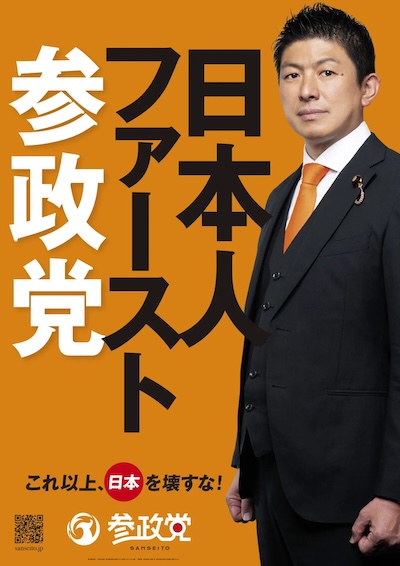

The Upper House election campaign has been dominated by an unusual issue: foreign residents of Japan. The upstart Sanseito Party, whose motto is “Japanese People First,” has made it one of the planks of their platform, saying that foreign residents enjoy privileges that Japanese people do not. The media has jumped on the issue since it’s more interesting that taxes, inflation, and defense budgets, and a fair portion of the public has seemingly been persuaded to find merit in the discussion. Consequently, the current government has already formed an “administrative body” to address the public’s concerns over foreigners in Japan.

Sanseito’s other policy proposals have received less coverage, but several media have studied the party’s draft Constitution, which Sanseito would endeavor to implement so as to replace the current Constitution if it ever became the ruling party. That’s a lot more ambitious than the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s Constitutional dreams, which are merely to amend the current charter so as to realize some of the LDP’s long-range goals and eliminate the American influence that has permeated the Constitution since it was drafted during the postwar occupation.

However, the media outlet that has looked at the draft document more carefully than any other is Akahata, the news organ of the Japanese Communist Party (JCP). Given how a good portion of the cognoscenti feel about the JCP, Akahata’s views are likely not going to be talked about much, but they bear scrutiny. In a nutshell, Sanseito’s Constitution is a direct throwback to prewar Emperor Worship and calls to mind the authoritarian policies that persisted during the early Showa era, when Japan was spoiling for war in its bid to dominate Asia. Nowadays, such policies would need to be approved through the mechanisms of a nominal democracy, but the Sanseito Constitution spells it out conveniently.

In essence, Sanseito’s Constitution prescribes for the people of Japan responsibilities rather than rights, meaning it’s the total opposite in purpose from the current American-dictated Constitution, which starts out defining the status of the Emperor as being merely a symbol of the nation and its people. Sanseito goes further, stating that the Emperor is the ruler of Japan on account of his divine nature. More specifically, in Article 3, the Emperor approves the prime minister and all Cabinet members, which the present Constitution also prescribes, but only as a formality. Sanseito implies that the Emperor can deny government selections, thus giving him political power that the current Constitution does not grant. In addition, sovereignty is invested in the state, which at first glance would seem to be similar in meaning to the current Constitution since it doesn’t invest sovereignty in the Emperor. But as Akahata points out, the current Constitution actually invests sovereignty in the people, not the state, because Japan is a democracy. Making the state the sovereign transfers all power to the government without necessarily gaining the approval of the people.

As for rights, the only one (kenri) mentioned in Sanseito’s Constitution is in Article 8, which guarantees the right of all Japanese people to “enjoy healthy, culturally rich lives,” a purposely amorphous pronouncement that can be interpreted almost any way. There are no mentions of respect for individual autonomy, equality under the law, freedom of expression, freedom of academic pursuit, or any of the other rights guaranteed by the current Constitution. Instead, the document stresses obligations that are deemed inseparable from civic life.

Akahata’s most palpable fear is about Article 16, which extends these obligations to the media. National policies must be covered “fairly,” a tacit threat to freedom of the press.

The cultural “richness” of being a Japanese citizen is discussed more fully in Article 7, which describes marriage and the family, a central pillar of the Sanseito platform. The article clearly states that marriage is a union between “a man and a woman,” and that a married couple must have the same name, thus making same-sex marriage and separate names for spouses unconstitutional. One of Sanseito’s policies is to “instill in girls” the sense that being a mother is their “highest calling,” thus implicitly advocating for women to stay home, keep house, and raise children full time, since such actions are central to the concept of the traditional Japanese family. Sanseito does not entertain the notion of any other style of “family.” Though Sanseito says it demands respect for women who prefer to be stay-at-home mothers and homemakers, it’s easy to wonder how far that respect goes. The party proposes granting households ¥100,000 a month for each child to encourage women to boost the birth rate and stay home, but would the deal extend to single mothers? Akahata wonders if Sanseito would also revive joshi shushi, a prewar set of moral tenets for girls and women that said almost explicitly that they should tolerate domestic abuse for the sake of the country.

Education will make it mandatory for young people to learn Japanese mythology in terms of how Japan was formed and founded. It also reinstates the Imperial Rescript on Education, which was instrumental before the war in instilling loyalty to the Emperor and the state. Article 7 says Japanese citizens must “uphold the Japanese sense of morality,” whatever that is, but whenever political parties start talking about the unique Japanese take on universal concepts, it usually means something akin to controlled consensus. Naturally, “patriotism” is central to education.

Akahata says that the Sanseito Constitution celebrates the prewar education system that fueled pro-war sentiments. Of course, any renunciation of war, probably the most significant feature of the postwar Constitution, is absent. Article 20 states that Japan has the right to arm itself and maintain a military force “for purposes of defense,” but Akahata believes that “defense” takes in the idea of collective defense, meaning that Japan could use its military in overseas conflicts in support of allies. In its platform, Sanseito has also pondered the possibility of severing its security relationship with the U.S. Japan should foster all the capabilities of a military power on its own.

The Sanseito Constitution also stipulates the conditions for citizenship: a Japanese national must “cherish” Japan and defend the country in order to make it safe for future generations; any violation of these precepts qualifies the miscreant as being “anti-Japanese,” effectively making that person unrecognizable as a Japanese citizen. How such determinations will be achieved is left to the imagination, but it’s easy to come up with worst case scenarios, including making blood the deciding factor as to whether someone is actually Japanese. This cult-like approach to Japanese citizenship is fully exercised in Article 10, which talks about “food culture.” Japan will be completely self-sufficient in food production in terms of seeds and fertilizers and centered on rice as the national staple. It should be noted that Sanseito initially appealed to certain progressive elements by promoting organic food production, but it also opposes climate change countermeasures such as carbon neutral and the Paris Agreement, presumably because these policies are deemed to have been foisted upon Japan by foreign elements.

This existential danger is addressed in Article 5, which states that “being Japanese” means not just “cherishing” Japan, but that the person in question has at least one parent who is Japanese, presumably by lineage; and the person’s “mother tongue” is Japanese, meaning that they grew up speaking Japanese. Akahata asked a lawyer about this article and he said that the present Constitution’s Article 14 guarantees equality under the law, so there is no need for a standalone law to ban discrimination. He believes that the language used in Sanseito’s Article 5 is discriminatory, which means if it’s in the Constitution then the Diet would be able to pass laws that are inherently discriminatory. Anti-foreigner bigotry would then be codified.