The edit of this 2022 Korean movie intended for release outside of Korea contains opening title cards in English that glancingly refer to the Sewon ferry accident of 2014, a disaster that claimed the lives of hundreds of children who were on a school excursion. Presumably, Korean viewers don’t need this information to appreciate the story they are about to watch, which focuses on two best friends who are somehow connected to the incident, though the first-time director, actor Cho Hyun-chul, keeps the viewer constantly off balance by circling around the matter. On the surface, The Dream Songs is a reverie on youthful ardor, the kind that best friends can feel to the point of infatuation, and is similar in tone and purpose to another recent Korean movie, So Long, See You Tomorrow, which also explores the fraught relationship between two adolescent best friends. The differences, however, are more striking. The pair in The Dream Songs are female, the one in So Long male. And while both movies trade in the kind of what-if fantasias that only cinema can deliver, The Dream Songs actually feels like a dream with its hazy, soft-filtered photography and narrative non sequiturs.

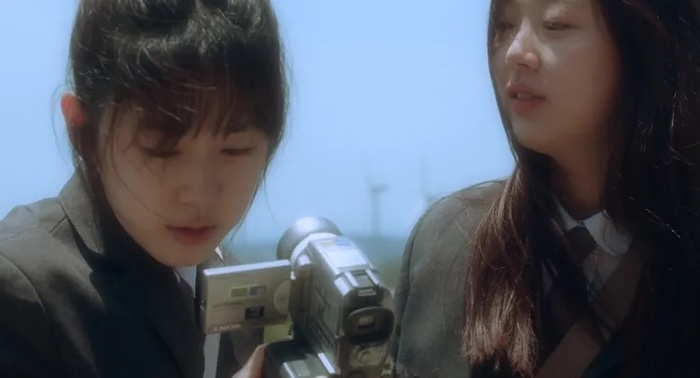

The movie starts with Se-mi (Park Hye-soo) at her school desk waking from a dream in which she imagines her BFF Ha-eun (Kim Si-eun) dead. Panicked, she begs the rest of the day off from her teacher to visit Ha-eun, who is in the hospital recovering from injuries sustained in a run-in with a bicycle. Relieved that her friend is not only alive but seemingly recovered enough to leave the hospital, Se-mi tries to convince Hae-un to join the rest of the class on the following day’s big school trip to Jeju Island. Hae-un is not going, and not just because of her injury. She doesn’t have the cash for it, so she and Se-mi concoct a plan to sell an old camcorder gathering dust in Hae-un’s father’s study. This plan leads to a series of misadventures that are sometimes confusing in their blend of intrigue and serendipity, but reveal Se-mi’s bond with her friend as something deeper than infatuation. At one point, she spies a note in Ha-eun’s diary about a mystery person whom she seems to have a crush on and commits herself to finding out who it is. This mission causes a rift between the two friends that results in Hae-un’s disappearance and Se-mi’s reckoning with her own immaturity, which peaks during a brilliantly staged scene in a karaoke box as Se-mi’s interpretation of an over-wrought love song turns into something hair-raising.

At some point, Cho, who also wrote the script, switches the nominal POV from Se-mi to Ha-eun and it takes the viewer a few minutes to adjust to the difference in sensibility. The movie becomes more melancholy, less impassioned in its emotional contours, and the viewer comes to an organic realization as to what the movie is trying to say—not tuned to plot machinations or sudden revelations but rather to a change in feeling that’s steeped in meaning. The digressions about lost pets and mistaken stalkers make sense not in a logical way, but in how they point to truths that should have been obvious all along. Part of the mystery has to do with teen attitudes. Cho lets his young actors live in their age-appropriate speech, which we in the audience can only partly penetrate; but not understanding what each remark is specifically supposed to convey doesn’t shut us out of their world because the movie’s meaning transcends language. It’s a dream that attempts to assuage the lingering pain of loss with memories of what love really felt like.

In Korean. Opens Nov. 14 in Tokyo at Shibuya White Cine Quinto (03-6712-7225).

The Dream Songs home page in Japanese

photo (c) 2021 Film Young Inc.