Whiplash thrillers have become a kind of cottage industry in B-movie Hollywood, confounding critics who, in service to readers, have to circumvent crucial plot points so as to not spoil the intended effect. JT Mollner’s Strange Darling is more inventive than your average whiplash thriller, which is only saying so much since once the big surprise happens there isn’t a whole lot to sustain the story except the jokes, some of which are so good as to seem wasted on this kind of rote bloody actioner.

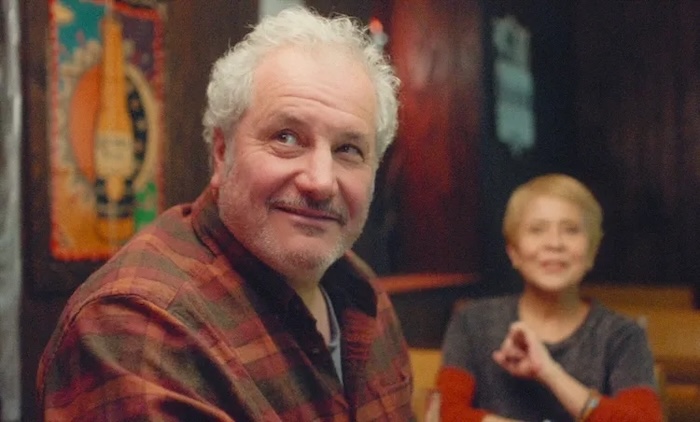

From the beginning we’re told what we will be seeing: the rampage of a serial killer somewhere in rural Oregon. The action picks up with a bloodied woman (Willa Fitzgerald) trying to outdrive and then outrun a mustachioed, cocaine-snorting guy (Kyle Gallner) with a shotgun. Neither of these people are given names, but that’s OK because the setup feels comfortably familiar. The first thing that throws us off is the structure. After the chase is interrupted mid-sprint, the story goes back in time, and thereafter keeps jumping around temporally, shedding details that are often just as confounding as they are explicatory. Mollner knows how to keep the audience for this kind of film satisfied and throws in lots of casual violence, kinky sex, and witty Tarantinoesque dialogue to keep things interesting, or, at least, not grindingly predictable. It’s a good-looking movie thanks to actor Giovanni Ribisi’s debut as a cinematographer. His dreamy atmospherics enhance the often perverse nature of the storytelling. An especially strange interlude that takes place in the forest cabin of an aged hippie couple (Ed Begley Jr., Barbara Hershey) is renedered surreally funny—”We’re not really into him,” Begley says when their unexpected guest spies an unfinished jigsaw puzzle of Scott Baio—and proves Mollner’s expertise as a scene-setter. And the pop music score by Z Berg is always a hoot.

But it’s pretty violent in ways that may be too gratuitous even for fans of the genre, thus undermining some of the script’s originality, as if Mollner had obligations he wasn’t sure how to handle and so threw everything he had into the gore. As witty and engaging as Strange Darling often is, the protracted ending is one of the most disturbing movie death scenes I’ve ever watched.

The switcheroo in Drop is less shocking and more conventional, and while the plot unfurls almost completely in real time, the work of keeping the various strands of the mystery intertwining is all there on the surface. Unlike in Strange Darling, the violence is contained, but the premise’s implausibility blunts the surprises.

A preface in media res introduces us to our protagonist, Violet (Meghann Fahy), who is being threatened with death by her husband. Though we don’t see the outcome of this encounter, we learn that it was he who died. It takes Violet two years to recover, during which time she has become a kind of celebrity DV counselor. On the night the story takes place she goes out on her first date since her brush with death, and she’s understandably nervous. Her sister (Violett Beane) is all encouragement and comes over to take care of Violet’s school-age son.

The setup is meticulous but pokey. As Violet arrives at the expensive Chicago restaurant where she’s to meet the man she met on an app, she comes into contact with various people in a casual, offhanded way—a too-friendly pianist, a helpful female server, a middle aged man who is also meeting someone he connected with online, and a shadowy handsome guy who mistakes Violet for his own date and keeps checking his phone. Finally, her own date, a photographer named Henry (Brandon Sklenar), arrives and as they sit down for drinks she starts receiving AirDrop messages on her phone telling her to do certain things, otherwise her son will be killed. Convenient video of a masked man skulking around Violet’s house are dropped to make the threats stick. Naturally, if she tries to tell anyone, the boy will die.

To say that director Christopher Landon does a better than average job with this material is saying little. The point is to keep the viewer hanging on every little clue as Violet tries to figure out who in the restaurant, including her date, is behind the threats and why they are making them. Once she discovers the real target of the mystery villain’s scheme she’s halfway there, but for some reason the reveals are less satisfying than they could be, mainly because almost all take place on phone screens that we have to read. Normally, I wouldn’t complain about the plausability of this kind of thriller, but the situation draws so much attention to the “why?” of the setup that everything else feels perfunctory.

Strange Darling now playing in Tokyo at Kadokawa Cinema Yurakucho (03-6268-0015), Shinjuku Wald 9 (03-5369-4955), Human Trust Cinema Shibuya (03-5468-5551).

Drop now playing in Tokyo at Toho Cinemas Hibiya (050-6868-5068), Toho Cinemas Shinjuku (050-6868-5063), Toho Cinemas Roppongi Hills (050-6868-5024).

Strange Darling home page in Japanese

Drop home page in Japanese

Strange Darling photo (c) 2024 Miramax Distribution Services, LLC

Drop photo (c) 2025 Universal Studios