Monster movies and so-called post-apocalyptic fiction are usually predicated on high-concept gimmicks. Sometimes the gimmick has a gloss of scientific credibility, such as the theory in The Last of Us that a killer fungus which has taken over the world emerged because of global warming; but in most other cases it’s an arbitrary convenience, like the idea in the Quiet Place movies that the murderous extra-terrestrials have super-accurate hearing but no visual capability. These phenomena thus become the overriding premise for all plot considerations. In Elevation, the insect-like monsters come from the ground, and the gimmick is that they cannot pass above 6,000 feet in elevation, which is why all of earth’s survivors live above that altitude. Director George Nolfi does an excellent job of creating a world that adheres to this premise without really making it believable. Why 6,000 feet? Why do the monsters only attack humans and no other life forms? Toward the end, we are offered something like answers to these questions, but they only bring up more questions.

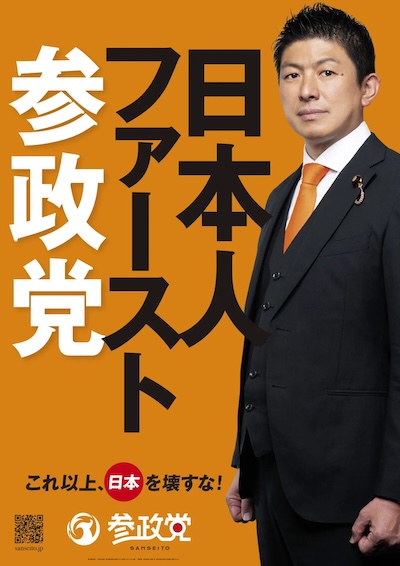

The setting is the Rockies, where Will (Anthony Mackie) lives with his 11-year-old son, Hunter (Danny Boyd Jr.), who, in the opening scene, sneaks below the danger line just for the opportunity to see how others might be living. It’s a poignant gesture that shows how isolation eats at the soul, especially for a little kid who lost his mother to the monsters, called reapers, after they emerged 3 years earlier. Though he just barely makes it back to the sparsely populated town where they live, he has another life-threatening problem: a respiratory condition that requires medicine that is almost out, thus requiring Will to venture to the city of Boulder in order to raid a hospital. In the end, he’s accompanied by two women, a hard-drinking physicist named Nina (Morena Baccarin), who spends her days testing a new type of ammunition she hopes will be effective against the so-far bullet-proof reapers; and Katie (Maddie Hasson), a stubborn outdoorsy type who is younger than Will and seems to have a beef with the older, endlessly cynical Nina. The bulk of Elevation involves these three trying to reach their destination and without passing below the safe line so as not to attract the attention of the reapers, and Nolfi is adept at ramping up the suspense without getting carried away. Along the way, the three principals are given ample opportunity to explicate their back stories, thus adding even more poignancy to their imperiled quest.

For all the skill and intelligence that’s gone into the production, Elevation still can’t quite shake the implausibility of its central idea, even with a final segment reveal that seems intent on doing that. In many ways it’s better than its ilk, but the fact that it belongs to an ilk that’s so ubiquitous in the first place only means it has a lot to overcome.

Opens July 25 in Tokyo at Human Trust Cinema Shibuya (03-5468-5551), Cinemart Shinjuku (03-5369-2831).

Elevation home page in Japanese

photo (c) 2024 6000 Feet, LLC